These students designed homes for unsheltered people. The community helped build them.

At 9 years old, Henry Steinle has done more for his community than most adults. He and his classmates designed four homes for people experiencing homelessness. In a couple of months, the first home — the one Steinle helped design — will be ready.

That’s right, the community is building houses designed by first and second-graders. Once built, they will be used as homes for unsheltered people in the students’ hometown, Lawrence, Kansas.

“It just feels really good,” Steinle said. He’s proud of his work and the changes he’s seen in the community. “My favorite part has been seeing it get built and seeing the community come together to understand the problem.”

What problem is that? Steinle can explain it as well as any changemaker with a passion for housing people. “There needs to be more affordable housing,” he said. “People want to live here because we have two colleges. We have a great basketball team, a great football team. The scenery is nice, and so we have people coming in from everywhere. The homeless population here is growing and growing and because of that, we need more housing. But we don’t just want housing. We need more affordable housing.”

What Steinle and his classmates have done to invigorate their community around this problem is nothing short of astonishing.

Madeline Herrera, Steinle’s teacher and founder of Limestone Community School, believes that as long as children have enough support, they have tremendous potential to contribute. “We don’t give children enough credit,” she explained. “We often tell kids they can be whatever they want to be. We tell them this on one hand, and on the other, our actions don’t support those statements. We tell them, you’re too young to have that conversation. You’re too young to solve that problem. I’ll tell you when you’re older.”

For the past 18 months, Herrera’s students have worked on the very “adult” problem of homelessness. They have demonstrated to the adults in their community what passionate, engaged problem-solving looks like. In doing so, they have come to understand their own value and ability to make life better for the people around them.

‘What if everyone could have a house?’

It all started with a book and a question.

Herrera read her students LaVar Burton’s “A Kids Book About Imagination.” In it, the author encourages young people to use the words “What if?” to explore and look for ways to solve problems in the world. When she finished the book, Herrera encouraged her students to brainstorm their own “What if?” questions.

“I was fully prepared for hilarious, fantastic first and second-grade questions,” she said.

But her students surprised her. The first question: “A student said, ‘What if everyone could have a house?’” said Steinle. “That was the main root.”

“I’ve been doing this for years,” Herrera said. “You would think that I would have, I don’t know, expected the gravity that students are able to hold, but no, it surprised me. The next question we got was ‘What if dragons were real?’ And then the third question was, ‘I want to go back to the first question.’”

Herrera and the students spent the next 20 minutes talking about homelessness in Lawrence. It was a conversation that a lot of adults aren’t comfortable having with children so young. “I get told a lot, ‘Are you sure you want to talk about this with kids?’” said Herrera. “What I tend to say is that we have decisions to make about how we talk with children. Just because we don’t talk about some of these topics doesn’t mean kids aren’t exposed to them. It doesn’t mean that they’re not coming to their own conclusions about them.”

“The children brought this project up,” she continued. “I simply allowed them to have the conversation. There was something that they were noticing in our town already.”

This problem of homelessness has daunted governments and nonprofit organizations for decades and centuries, and in 20 minutes, Herrera’s elementary school students came up with something they could do about it.

“They felt very confident that they could get everyone in our community a home,” she said. “So I asked, ‘What does that look like? How are you going to do that?’ And they’re like, ‘We’re probably gonna have to build homes.’”

Children learn better when they’re passionate

In her school, Herrera uses a project-based learning model. Students look for real-world problems they would like to solve and then, after a lot of research and interviews with knowledgeable people, they create their own projects to address the problems. Every project has a meaningful close, such as a presention to experts.

“It’s not just presenting to the teachers, not just presenting to parents,” said Herrera, “but people that could take this idea further or would be in some decision-making power or experts in the field.”

Henry’s father, Sean Steinle, said this was a big reason he sent his son to Limestone Community School. “We were a big fan of the idea of project-based learning as opposed to rote memorization. They’re using skills that they’re learning in something they’re passionate about.”

The kindergartners at Limestone are currently working with local artists to create a mural at a busy bus stop in their neighborhood. Limestone’s fifth graders recently wrapped up a podcast series in which they interviewed different people about the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Some of Herrera’s students created a five-year sustainability plan for their school.

A project too huge to believe

The home design project was going to be no different. The plan was to end with presentations to local experts. Herrera invited speakers to come talk with her students about homelessness. She enlisted the help of a local architecture firm that sent four architects to her class every week for months. They helped students design four liveable, comfortable homes.

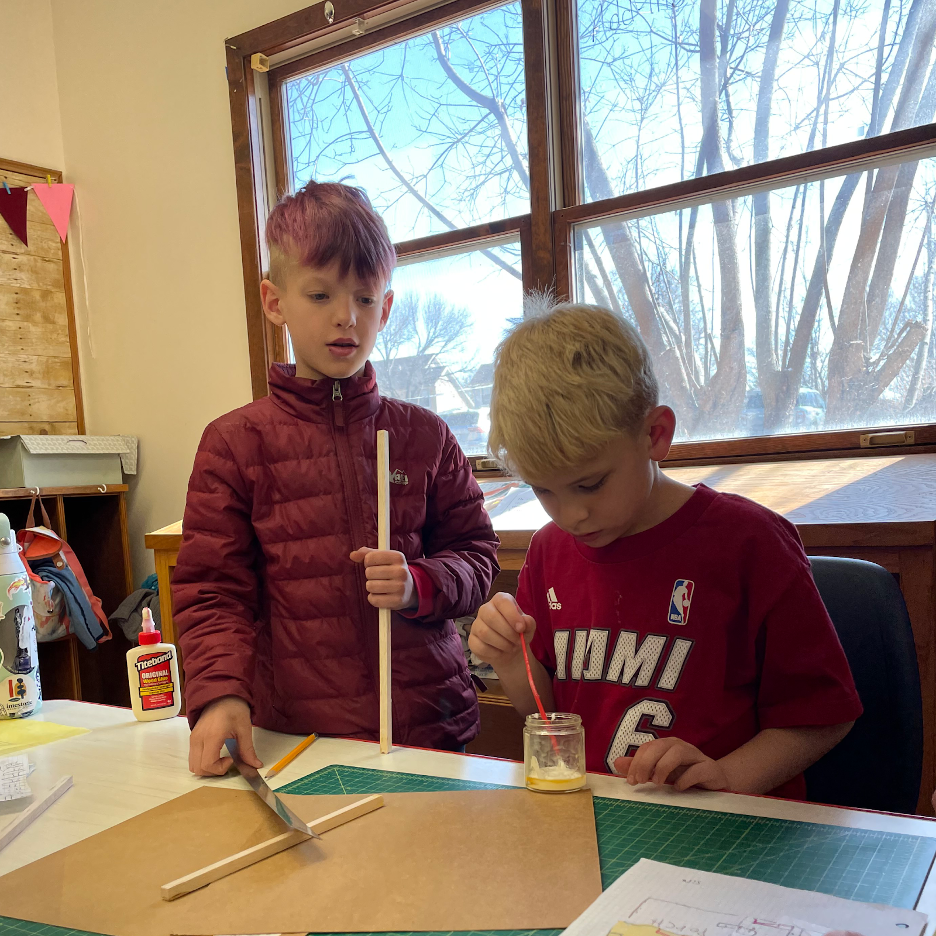

“My part was, at first, when we met with the architects,” said Henry Steinle. “We drew what we wanted the house to look like, and we kind of drew our models. Then we put together a cardboard and wood model of all of them.”

The students started showing their models to experts in the community. One of those experts was Rebecca Buford, executive director of Tenants to Homeowners, a community housing development organization. Buford had heard about the project from a parent. “I’m thinking this whole time of high school students,” she said, and when the parent told her they were elementary school students, “I was hooked. … For me, it was about community education. Who could better educate than first and second graders?”

When Herrera called Buford and asked if she would be willing to come see the students’ presentation, her answer was, “Yes, absolutely. I would love to do that. And how many plots do you want?” She then offered two plots of land to build the houses on.

At first, Herrera was stunned and skeptical. “I need you to understand that I’m about to go walk into my classroom,” she said, “I’m gonna tell those students. So please don’t say this if you don’t really mean it.”

Buford was serious. She prepared the paperwork for a partnership with the school. Herrera went back to her classroom and told the students they were going to actually build their houses.

“I was very shocked and excited,” said Henry Steinle. “I was also kind of nervous, but I was really excited that we actually designed a house that’s going to be able to be built. I have a big memory of the whole class standing out of their chairs and jumping around. It was a lot of fun when we first found out.”

When he told his parents, they didn’t believe him. “I think we knew that they had architects coming in, and we just thought, how cool,” his father said. “And then one day, just so matter of factly, Henry’s like, ‘Yeah our house is gonna be built.’ I was like, ‘Ok, that’s cute.’ Legitimately, it was so huge that I didn’t even believe it.”

When he heard the news from Herrera, “My jaw dropped.”

Young kids teaching the community about homelessness

Shortly after Herrera’s students began working on their designs, an arctic blast came through Lawrence. Some people experiencing homelessness set up a tent in a field on Limestone’s property.

When students saw the tent, the work they were doing became more real to them. “It drove home the point that this work is so important,” said Herrera. “They really wanted to create the best plans they could because they believed that if people heard about what they were doing, they’d want to learn more and maybe they’d be inspired to take action.”

According to Buford, the homelessness crisis in America is especially acute in Lawrence. “Forty-six percent of households qualify for our services,” she explained. This project and the little people executing it have caused many locals to take a fresh look at the problem.

Community members and organizations have been eager to support the students. The architecture firm donated the first two house plans. Another company supplied the gravel for the first house’s foundation. A local design school held workshops about different construction materials for the students and helped them choose what they wanted in their houses. A native plant expert coached them as they made a landscaping plan. And when word got out that the project needed an arborist, Herrera found herself fielding multiple unsolicited bids — all offering their services for free.

The first home will be completed this summer. Henry Steinle and his classmates will help paint the interior. The second home is planned to begin in the next year. Two local organizations are in conversations with Herrera about building the last two homes.

“I feel like they are starting to understand the main problem,” said Henry Steinle about adults in the community. He said that seeing first and second graders design and build affordable housing has made them notice.

His dad is certainly paying more attention. “I’ve lived in this town my entire life, and in two years, they have been more active in local government and community service than I have in my entire life.”

More than anything, Herrera has been impressed by the children’s openness as they have learned more about homelessness. Along the way, they’ve shed some of their own biases. When a classmate revealed that he had been unhoused once, several students were startled by the idea that a kid could become homeless. However, this new information about their classmate didn’t make the other kids think less of him. Instead, he became the class consultant for what homelessness is like.

“Children have a lot of innate nobility, an innate compass of where they think things can go,” said Herrera. “They have more creativity and imagination to solve these problems. When you open up the space for them to be a child and join in these conversations, it creates a strong foundation for them to internalize and say, ‘I am valued as a child in this community.’”